A director faces a plethora of choices when he or she sets out to make a movie. In this age of advanced modern technology, it is often assumed that one decision no longer needs to be made: whether to film in black and white, or in colour. Colour can add richness and brilliance to a film; try and imagine the Emerald City or the Yellow Brick Road from the famous The Wizard of Oz in black and white. The vast majority of films released these days are presented in colour, yet every year, a few black and white gems still make their appearances. This year, the Best Picture Academy Award nominee Nebraska comes to mind, along with last year’s Toronto International Film Festival favourite Frances Ha. There are a few reasons why a director may choose this form in which to present his or her art, a few of which will be explored here.

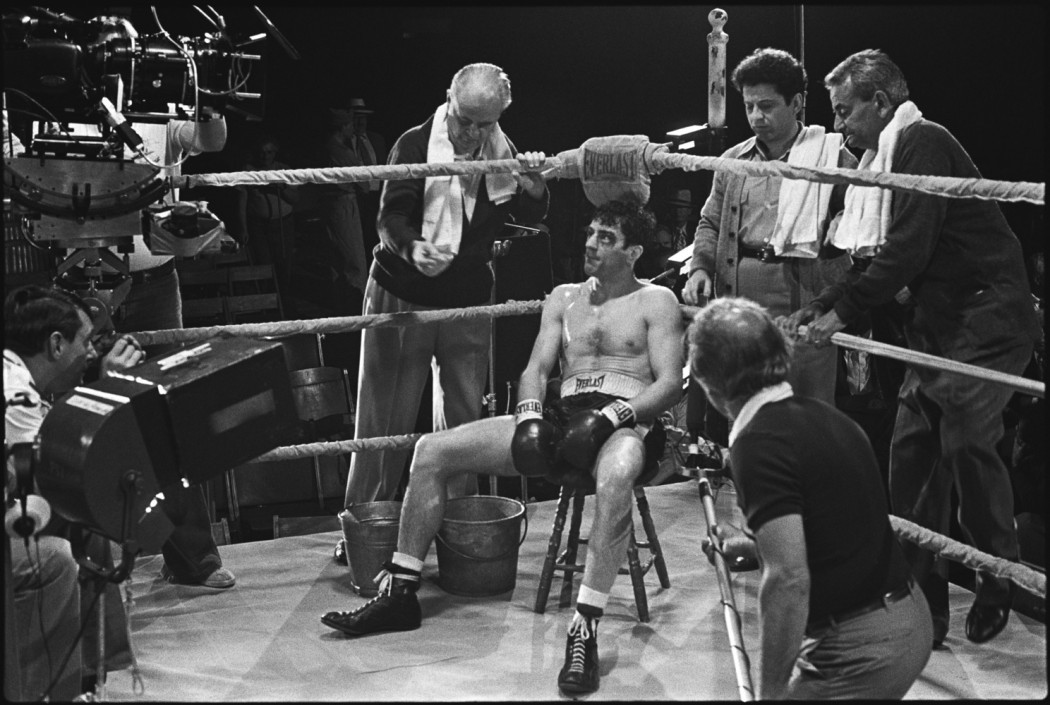

One of the most common reasons why black and white filming is favoured over colour is to convey a bygone era. Take the famous Martin Scorsese boxing biopic Raging Bull (1980). Although this film was released in the eighties, it is set during the forties. Colour movies were certainly being created before this time, notably The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind, both in 1939, yet the black and white filming still feels appropriate to depict the former time. A viewer is transported to this age in a way that they wouldn’t be if they viewed it in colour. Interestingly, Scorsese claims to have another reason to present his film in black and white: the graphic and bloody violence in the movie would not have passed the censorship board at the time, which allowed the film an R rating in black and white. Personally, I believe the necessary violence in this film to be little diminished by the lack of colour, as pitch black blood stands out in stark contrast to pale white skin.

Another film that effectively uses black and white to evoke an era is Gary Ross’s whimsical fantasy Pleasantville (1998). This movie begins in colour when it depicts the present day, yet when its protagonists find themselves swept into a fifties-era television show, the film becomes black-and-white just like the program they watch. Colour is used as a strong and highly symbolic visual motif in this film as well. As the siblings introduce joy and freedom to the restricted citizens of Pleasantville, people begin to turn colour, symbolizing their liberation. By the conclusion of the film, the transformation back into colour is complete. The black and white filming is therefore wholly necessary in order to achieve the powerful visual symbolism, as the colourful new lives can only be attained to replace the colourless ones that appear stark in comparison.

Colour may also be used to highlight certain objects or changes in time. Steven Spielberg’s 1993 classic Schindler’s List is famously shot in black and white, with a few key scenes and images appearing in colour. The film opens in colour, yet promptly fades to black and white, symbolizing the audience’s journey back in time as black and white film represents the World War Two era. Early in the movie, a little girl is seen in a red coat, which stands out in a sea of grey. Later, this same coat catches audience attention once again, but now it is on a corpse in a pile of dead bodies. The devastating, symbolic imagery only works due to the bright colour of the coat that makes it recognizable and noticeable. Spielberg has stated, “The Holocaust was life without light. For me, the symbol of life is colour. That’s why a film about the Holocaust has to be in black and white.” In this way, Spielberg uses the very colour of his film to symbolize something greater: the lifelessness of the events that he portrays. Indeed, many are only able to associate the Holocaust with the historical black and white pictures to which they are exposed, and it is therefore appropriate to continue this tradition and present the audience with a world they can recognize, if hardly understand.

Black and white filming does not always have to be used to represent devastation, however. Michel Hazanavicius’s Best Picture Academy Award winning film The Artist (2011) uses black and white filming for very different purposes. Here, the old fashioned technique is used to create both nostalgia and charm. This film is about actors in the era of silent film, and is itself a part of this almost forgotten genre. It therefore makes sense for this throwback film to use a throwback technique; a silent picture in colour would definitely present an interesting anachronism, but that is not the goal here. Instead, this sweet movie allows one to feel as though they were indeed part of a simpler time, when life was less complicated and decisions actually were “black and white.”

Just as The Artist uses black and white filming to reference the silent pictures that were its inspiration, films such as Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha (2012) use this technique to allude to other works as well. Throughout this movie, reference is made to many classic films, particularly those of the French New Wave movement such as Jules and Jim (1962) and The 400 Blows (1959). One cannot now go back in time and create a film during this era, so instead, the director chose to integrate cues and techniques that alert a viewer that this is the type of film that he is aiming to create. The black and white filming also calls to mind Woody Allen’s 1979 classic Manhattan, famously shot in black and white. A film attempting to emulate a specific genre often takes its cues from said tradition, and Frances Ha achieves this feat brilliantly, remaining modern and highly relevant even as it channels the classics.

Finally, black and white filming may be used to create a movie world that is separate from the one in which we live. This year’s wonderful film Nebraska, by Alexander Payne, displays a world so similar to the average individual’s that it at times seems to be a depiction of our own lives. By filming the piece in black and white, the world presented is differentiated from the colour one that we see every day through our own eyes, and a viewer is gently reminded that this piece is, indeed, a fictional film that is not rooted in our lives but is timeless instead. The film’s studio, Paramount Vantage, was actually vehemently opposed to shooting the film in black and white, yet Payne got his way, and the film got it’s Oscar nomination.

A note must also be made about a disturbing trend often seen these days. While forward thinking directors are embracing the use of black and white filming, many studios are releasing black and white classics with colour added in. Watching films such as It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) in colour today feels wrong and inappropriate. Late and legendary film critic Roger Ebert famously lamented the colourization of such movies, and he makes a solid point. There is something pure about the crispness of black and white that is lost when colour is added, often poorly and cheaply. We do not take colour films and switch them into black and white, so the same respect should be shown for black and white classics.

There are many reasons why a director may choose to film in black and white as opposed to colour. Some hope to evoke an era or reference past films, while others aim to inspire nostalgia or create a world separate from our own. Often, directors use black and white images in symbolic juxtaposition with those in colour, while still others use black and white for its functionality, as they are able to highlight key elements or even escape censorship. I enjoy black and white film for the overall mood that is conveyed when it is used effectively. Simply because the new technology to create brilliant colour exists does not mean that it must be used every single time, and it takes a very special director to realize this truth and exercise the necessary restraint.

No Comments